Best artists of all time: Gustav Klimt (1862 – 1918)

Many artists have painted with vibrancy and vivaciousness down the centuries, but few have done so quite like Gustav Klimt, whose paintings are suffused with bright colours, and whose subjects leave viewers sighing with admiration. The natural feminine beauty and landscapes that spring into life before the viewer’s eyes elicit the feeling that Beethoven wanted to express in his ‘Ode to Joy’.

Gustav Klimt was born in 1862 in a district of Vienna on the fringes of the famous Viennese woods, into the family of an engraver and jeweller (this is one of those rare occasions on which the ‘mandatory’ information about an artist’s parents really is important). What is interesting is that both of this outstanding artist’s brothers chose the same path in life. After picking up some initial drawing skills from his father, Gustav set off to study at an arts and crafts school that was not particularly prestigious, where his chosen subject was architectural painting. On completing his studies there, Gustav chose not to turn himself into a rebel creator but instead set about working in his field of specialization, engaging mainly in design activity. He created frescoes for theatres in Karlsbad, Rijeka and Reichenberg (Klimt also drew the images on the curtains for several theatres).

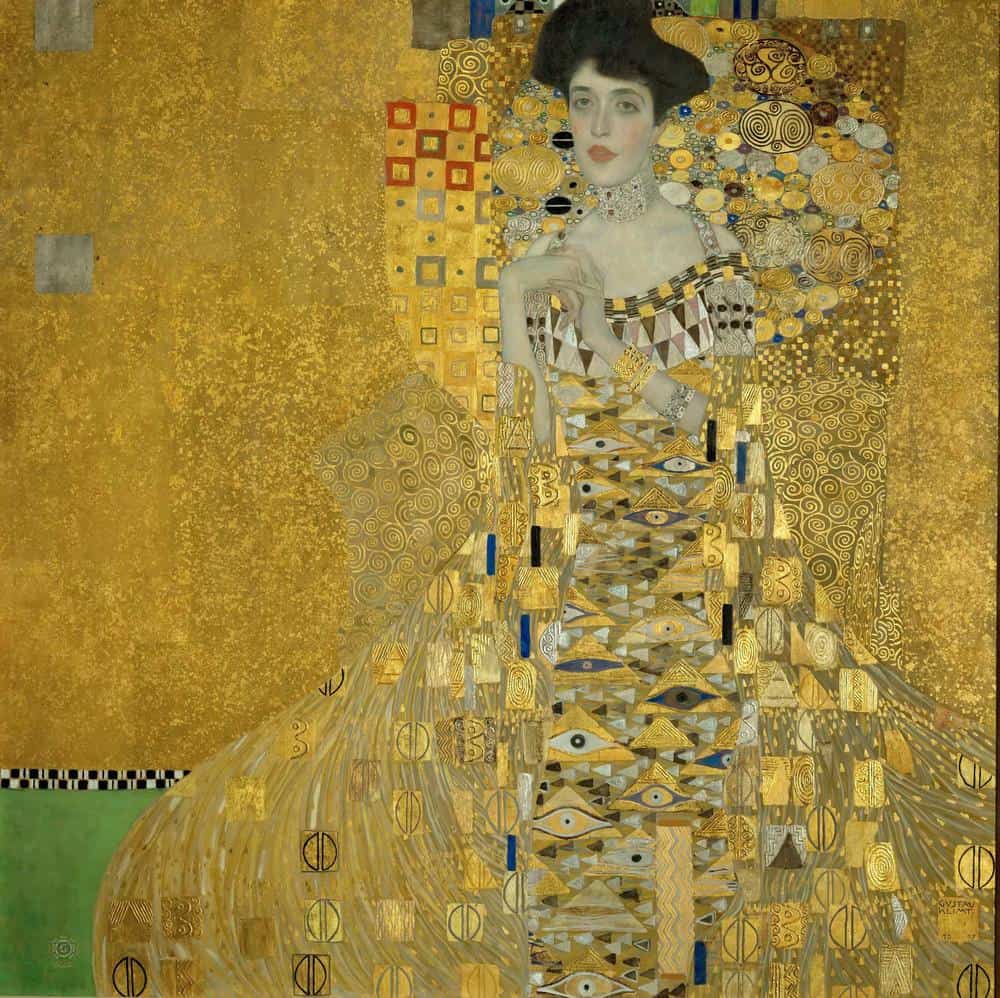

Though this master achieved fame thanks to later canvases, the paintings he did in this period of design work is just as highly thought of by viewers and critics as his famous canvases; and there have only been a handful of artists in history about whom one can say this (the only one that comes to mind whose work is comparable in scope is Diego Rivera). Getting by on commercial commissions for a long time, Klimt always remained true to himself even in this work, and this holds true not just for his work as a designer, but also for his creation of a an engaging series of portraits of some of Austria’s bohemian creatives. One can see the artist’s new style taking shape in these portraits: whilst keeping the features of the face and the proportions of the body as ‘classical’ as can be, he gradually alters the nature of the backdrop so that it is to his liking; it is because of this that the ‘fire’ of his imagination leaps onto his characters’ clothes, so as to get right up close to all that is most sacred…

One of the important milestones in the artist’s oeuvre was the work he did on designing the capital’s Art History Museum. The artist was awarded the imperial ‘Golden cross’ in 1988, and in 1892, after the death of his father, it fell to him to provide for the family. At that time, Gustav was just starting to develop his own inimitable style – what we might call his ‘brand’ of painting. In 1897, Klimt became president of the Viennese Secession – an arts association that had no manifesto and was united by nothing more than a shared desire to develop new styles, conduct an artistic exchange with artists from other countries and promote the creative output of the association’s members. In this period, Klimt would create a number of landscapes that went on to become classics of the genre.

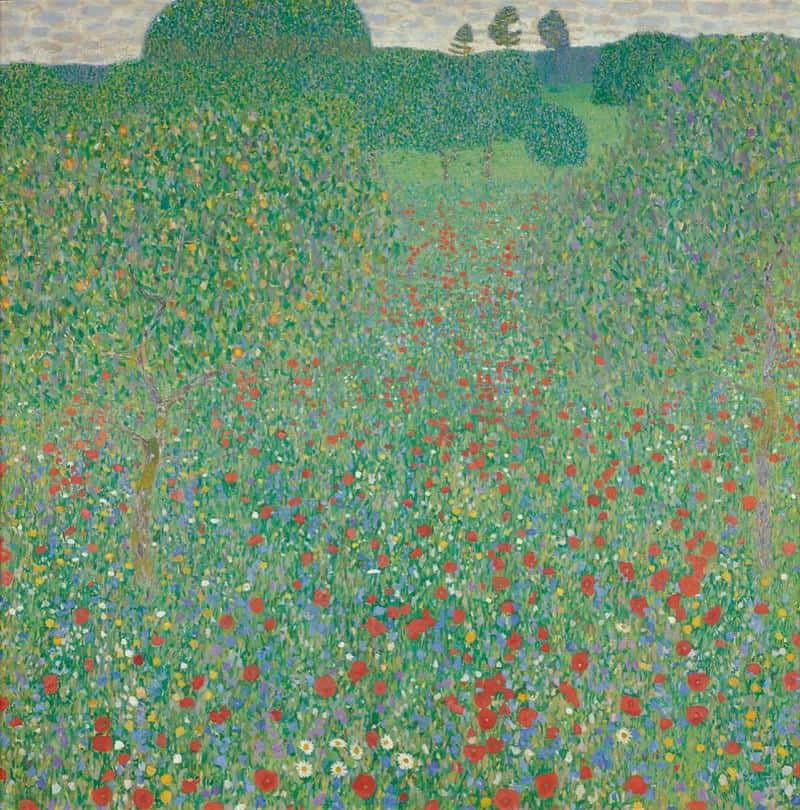

Klimt’s landscapes can be likened to the Impressionist works of Monet, but the stunning level of detail on the canvas is taken to new extremes here (‘Poppy Field’). The brush strokes become smaller in size and, if the viewer lets their gaze become unfocused, the canvas is at risk of disintegrating into tiny ‘pixels’ of paint; this in fact gives life to the paintings, as though a light gust of wind is rustling the grass and the leaves of the trees around the viewer. It can almost seem as though someone has taken apart some of Pollock’s Absurdist splattered images and, by reassembling them a different way, like a Rubik’s cube, achieved the effect that would later be achieved, in a somewhat different solution, by Klee, whereby a multitude of what seem at first to be insignificant, fragmented elements come together to create the painting itself. Klimt was undoubtedly far removed from Abstractionism and Surrealism, but the master’s extraordinary technique compels us to seek to make such unusual comparisons. Some of his paintings (such as ‘Cottage Garden with Sunflowers’) are akin to those of Gauguin by virtue of their post-Impressionist fervour, while others (such as ‘Two Girls with an Oleander’) can even be likened to the work of the pre-Raphaelites. Does that give you a sense of the sheer variety in his oeuvre? Incidentally, some of Klimt’s pencil sketches (such as ‘Reclining semi-nude with her face half-covered by her hand’) can accurately be described as works that prefigured the emergence of Schiele.

Klimt was an artist who was constantly searching for something. If one were to look at his early artistic output, it would be hard to imagine that these works and the canvases from the famous ‘Golden period’ were painted by one and the same man. The artist didn’t plan to linger too long ‘on gold’, incidentally – but sadly he was prevented from moving further by death, which took him when he was still relatively young. The classical construction of figures, familiar composition, and ‘traditional’ subjects that were typical of his early career fell away somewhat as time went on. By all accounts, though, it was his work as a designer that had a major influence in terms of shaping this master. The dividing up of the foreground and the background, with the latter subsequently ‘washed’ (the reason for this lay in the artist’s laziness, and in a desire to highlight what was happening in the foreground in this way) is very characteristic of Klimt.

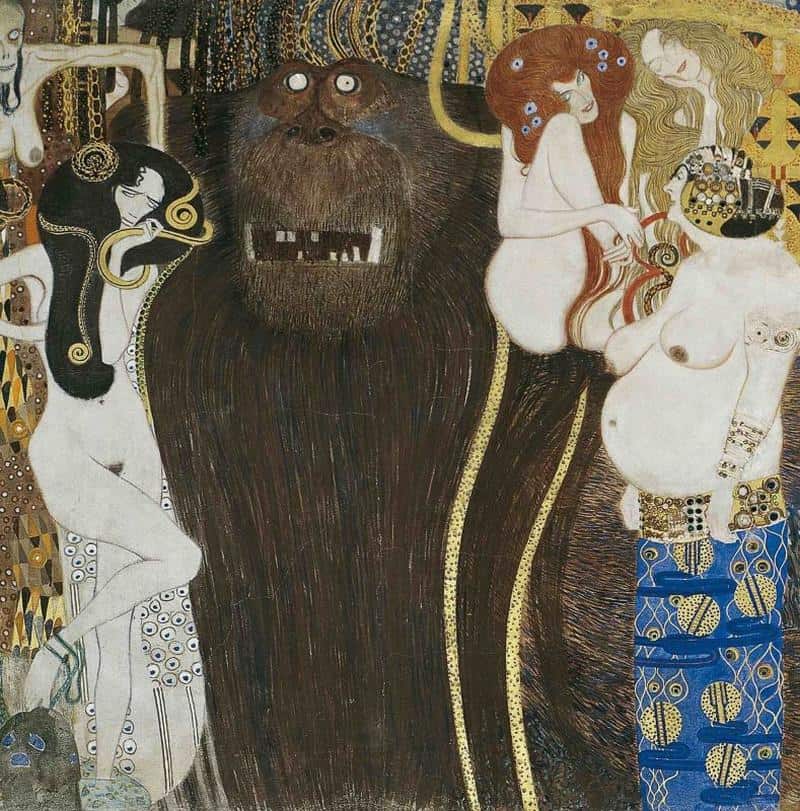

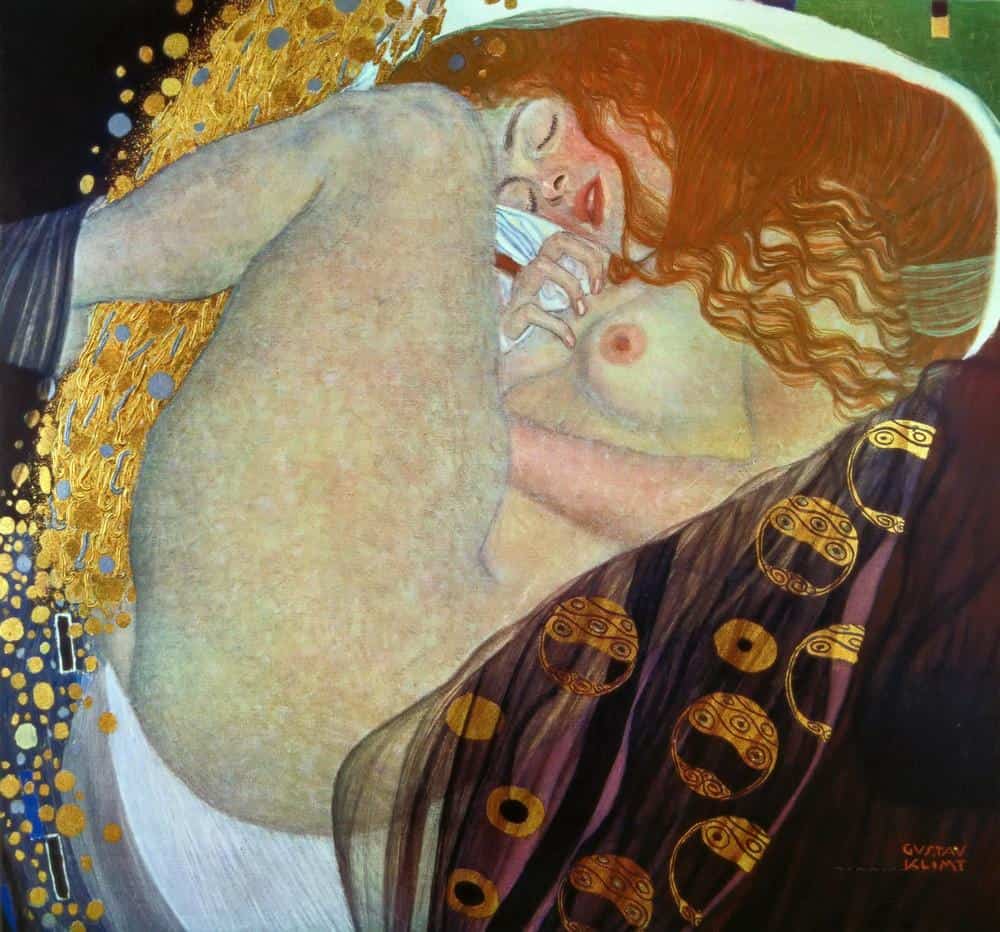

This becomes most obvious when a human figure appears “in the frame” – the artist promptly forgets what is going on in the background. Nature is life, and that is why it interests Klimt, but for him, woman is the highest embodiment of life – and that’s why male figures are so seldom seen in his paintings. Klimt’s world is like an inverted Greek theatre, in which all the roles (both the positive ones and the negative ones) are given to women. Woman is the life-bearer and the bestower of love; she is also death – not a sad and brutal death, though, but a reasonable one, with no biases.

Nudes appear very frequently in Klimt’s later period, and the master received condemnation for this from all quarters: society, the authorities, the clergy. These criticisms were ridiculous, though; and the point here is by no means that for the modern viewer, such a level of ‘eroticism’ is something we’ve long since grown used to, nor in the age-old complaint that “Michelangelo painted nudes too!” Only a blind person could fail to perceive, in the nakedness of Klimt’s women, a sensitivity that is far removed from deliberate lust. The tranquillity, romanticism and openness of his heroines make them incapable of looking obscene, even if they were to be put on show in a monastery. (It should be noted, in all fairness, that the artist sometimes went a lot further in his pencil sketches). It is also worth saying a few words about the master’s female types, for they were many and various. There are temptresses in their prime, and there are modest, shy women. There are blondes, brunettes and redheads. There are thin women and plump women. They all have one thing in common: their imperfection. Absolute beauty is alarming and repellent, and it compels us to go looking for flaws; Klimt, though, was an artist of true beauty: beauty that is out of proportion, asymmetrical, natural.

This brilliant artist passed away on 6 February 1918 due to pneumonia and complications following a stroke. Gustav was just 55 years old when he died.